[Scientific Qi Exploration 气的科学探讨]

The Twelve Tendino-Muscular Meridians. Part 1

Marty Eisen Ph.D.

1. Introduction

These Meridians are called Tendino-Muscular Meridians since their paths pass through (Jing) the depressions and planes between the muscles and tendons. The character Jin represents something forceful inside the body and so includes both muscles and tendons. They are also known as Sinew Meridians (Jing Jin) or Channels, Muscle Meridians or Areas and Sinew Channels.

These Channels were first described in the Yellow Emperor’s Inner Classic (Huang Di Nei Jing) composed of two texts. The second text, the Spiritual Pivot (Ling Shu), outlined the pathways and functions of the Jing Jin in Chapter 13. This chapter was written between 100 BC and 100 AD (1). The description used the characters and terms that were in use at that time. This led to ambiguities in translations and so the theory of the Jing Jin is not as well agreed upon as for the other Meridians.

The Jing Jin don’t appear in the Classic of Difficulties (Nan Jing), written around 200 AD. They are also not mentioned in medical texts of succeeding dynasties, which have been translated into English. Modern Chinese texts contain little additional explanations to that in the Ling Shu. Western texts present the same material found in the modern Chines texts. Some authors add speculations about the Jing Jin.

There are 12 Jin Jing, one for each of the 12 Principal Meridians. Their pathways begin at the extremities of the limbs and travel to the trunk and head. They travel superficially and don not reach the Zang and Fu Organs. Being superficial, they only contain Wei Qi. The three Yin Muscle Meridians of the leg connect with the genital region. The three Yang Meridians of the leg ascend to the lateral, anterior and posterior surfaces of the trunk. The three Yin Muscle Meridians of the hand connect with the thoracic cavity. The three Yang Muscle Meridians of the hand connect with the angle of the forehead (2). Their pathways will be described in detail below.

One of the earliest modern illustrations of these pathways appeared in a text published by the College of Traditional Chinese Medicine in 1974 and appears in (2). The figures use a wide, striated band to indicate the pathways (4, 5). These bands narrow to points to probably indicate the joining to a bone or sinew. Other texts use narrow lines to illustrate the pathways of the Jing Jin (3). The variations in the pathways indicate that there are independent interpretations of the original descriptions in the Ling Shu.

The body’s Wei Qi field is the first line of defense against External Pathogens. The second lines of defense are the Muscle Meridians. The Collaterals are the third line of defense. If the Pathogenic Factors cannot be redirected or purged from the Collaterals, they will advance into the Regular Meridians, which are the last line of defense before the Pathogenic Factors advance to the Internal Organs (5).

The Sinew Meridians (Jing Jin) are the external source of energy for the muscles. They control the movement of the extremities, extending and flexing the joints. They hold the body erect. They protect the body from trauma. In Chinese medicine, Fibromyalgia is a disease in which the internal organs are well but the Tendino-Muscular Meridians are affected

A neurological function of the Jing Jin is to control instinctive reactions in the body, like withdrawing the hand after touching a hot object. They are also responsible for emotional moods such as feeling one way today, but not feeling the same over time or for any particular reason

2. Wei Energy Cycle in the Jin Jing

The cycle of Wei energy in the Jin Jing is different than the cycle of Qi in the Principal Meridians (3). In the Jin Jing the energy flows in the Yang Meridians during the day and in the Yin Meridians during the night. It starts in the Bladder Meridian and flows up to the inner canthus. The arrival of the Wei Qi opens the eyes upon awakening in the morning. From the Bladder Meridian the circulation continues into the two other leg Meridians and then into the three Yang arm Meridians. In the evening it flows in the Yin Meridians and then back to the Bladder Meridian to complete the cycle.

The actual cycle is: Leg Tai Yang (B), Leg Shao Yang (G), Leg Yang Ming (S), Hand Tai Yang (SI), Hand Shao Yang (SJ), Hand Yang Ming (LI), LegTai Yin (Sp), Arm Tai Yin (L), Leg Shao Yin (K), Arm Shao Yin (H), Leg Jue Yin (Liv), Arm Jue Yin (P), and then back to the B to complete the cycle.

In (6) the Wei energy cycle is described as above in the first eight Jing Jin, but then from the L it flows through the LIV, P, K, H and back to the B to complete the cycle.

The author in (3) states that the Ling Shu (Chapter 13) specifies that each Tendino-Muscular Meridian corresponds to a specific month and is most likely to exhibit signs of disturbance during that particular month. For instance, the Bladder Jing Jin is related to February. Trouble with the Bladder Jing Jin is called February Rheumatism. The actual months are:

B February Sp August

G January L November

S March Liv September

SI May P October

SJ June K July

LI April H December

Since the Jing Jin pathways are superficial and influence the muscles and tendons, their symptoms would be those of joint and muscle disorders. As they contain only Wei Qi, which is mainly Yang or a kinetic nature, they are easily influenced by solar and and earthly factors. The common complaint: “It’s going to rain, I can feel it in my joints.” cannot be explained by western medicine, but can be explained in Chinese medicine in terms of the Jing Jin.

Low (3) claims that all the Jing Jin begin at the Tsing ( or Jing-Well) Points of their corresponding main Meridian. These points lie at the beginning or end of each Meridian,

The following descriptions of the pathways of the Tedino-Muscular Meridians follow (2).

3. The Bladder Jing Jin Pathway\

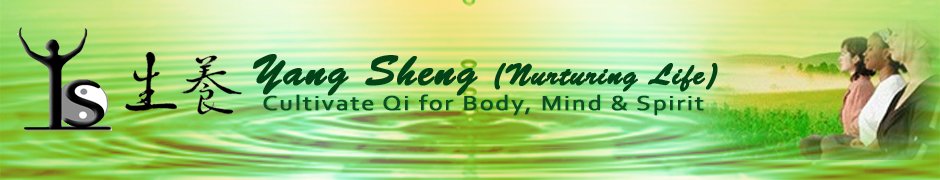

Figure 1 The Bladder Jing Jin Pathway

It begins at the little toe, ascends to attach at the external malleolus and the at the knee (as indicated by the numbers 1, 2, 3). A lower branch separates and runs below the external malleolus, extends to the heel and ascends to attach at the lateral side of the popliteal fossa (4, 6, 5). Another branch separates at the meeting of the lateral and medial heads of the gastrocnemius muscle and ascends to attach at the medial side of the popliteal fossa (4, 6, 7). These two branches merge in the gluteal region (8) and ascend along the side of the spine to the nape (9), where a branch emerges and runs to the root of the tongue (9, 10). The diagram is not precisely drawn since the nape (9) is at the height of the posterior hairline. The straight portion attaches to the occipital bone above the neck (11), ascends to the top of the head to attach to the bridge of the nose (12, 13). Another branch spreads around the eye (14) and attaches below and beside the nose (15).

Another branch emerges from the straight portion beside the spine, about the level of the lower border of the spinous process of the sixth thoracic vertebra, travels towards the axilla and splits into two. One branch (16) going to LI 15 (Jian Yu, anterior and inferior to the acromion in a depression found with the arm abducted.). The other branch (17) enters the chest from below the axilla, emerges from the supraclavicular fossa (18) to attach to G 12 (Wan Gu, in a depression posterior and inferior to the mastoid process.). Another branch also emerges from the supraclavicular fossa, traverses the face to the side of the nose (19).

Knowledge of the Bladder Jing Jin Pathway helps recognize the following symptoms of February Rheumatism (3): paralysis of the little toe, swollen heel pain, popliteal fossa spasms, spinal curvature, muscular spasms in the posterior neck, unable to raise shoulders, painful cramps in the axilla extending to the supraclavicular fossa; stiff shoulders.

4. The Gallbladder Jing Jin Pathway

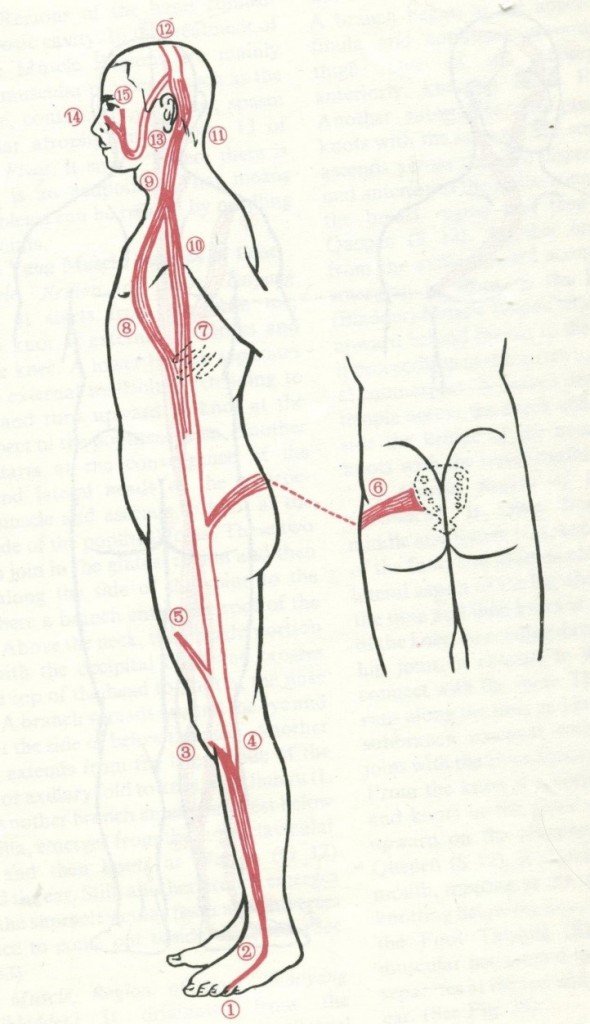

Figure 2. The Gallbladder Jing Jin Pathway

The Pathway begins at the fourth toe and attaches at the external malleolus (1, 2). It ascends along the lateral side of the tibia and attaches to the knee (2, 3). A branch begins at the superior part of the fibula (4) and ascends along the thigh. Next, a sub-branch (5) runs anteriorly attaching above S 32 (Fu Tu, on a line drawn between the lateral border of the patella and the anterior superior iliac spine, in a depression 6 cun above the superior border of the patella.). Another branch (6) runs posteriorly and attaches to the sacrum. The straight branch ascends across the ribs and forks. One sub-branch travels to the breast region (8) and the attaches to

S 12 (Que Pen, in the supraclavicular fossa, above the superior border of the clavicle, 4 cun lateral to the midline.). The other branch of the fork (7) ascends toward the axilla, crosses the clavicle, passes in front of the Bladder Jing Jin and continues upward behind the ear to the temple (10, 11). It continues upward to the vertex of the head to join the Gallbladder Jing Jin Pathway from the other side of the body (11, 12). Another branch descends from the temple across the cheek and attaches beside the bridge of the nose (13, 14). A sub-branch attaches to the outer canthus (15).

Some symptoms of January Rheumatism (3) are: spasms and paralysis of the fourth toe, spasms of the lateral side of the knee with difficulty in bending the knee; spasms of the popliteal fossa, anterolateral thigh and the sacral area in the lower back; disturbances can cause pain in the lateral abdomen and hypochondriac regions; muscular spasms in the mammillary, supraclavicular fossa and neck regions.

5. The Stomach Jing Jin Pathway

The Pathway, Fig. 3, starts from the second, third and fourth toes and attaches at the dorsum of the foot and ascends along the lateral aspect of the leg and forks.

One branch disperses along the tibia, and then attaches at the lateral aspect of the knee (1, 2, 3). Ascending, it attaches at the hip joint (4) and extends to the lower ribs to connect with the spine (4, 5).

The other branch runs along the tibia and attaches at the knee, where it forks (6).

One subbranch (7) connects with the fibula and joins the Gallbladder Meridian.

The other branch ascends from the knee ascends the thigh and attaches in the pelvic region (6, 8, 9). Dispersing upwards on the abdomen and attaching at S 12 (Que Pen) (9, 10, 11), it extends to the neck and forks (12).

One branch extends to the mouth, meeting the side of the nose and attaching below the nose (12, 13). Above, it joins the Bladder Meridian to from a muscular net around the eye.

The other branch separates at the jaw and attaches in front of the ear (15).

Figure 3 . The Stomach Jing Jin Pathway

Some symptoms of March Rheumatism (3) are: spasms of the third toe, the foot can feel hard and have jumping sensations, swollen anterior upper thigh, spasms of the rectus femoris, scrotal swelling, spasms of the abdomen extending to the supraclavicular fossa and cheek; sudden misalignment of the upper and lower jaws.

Marty Eisen, PhD, is a retired scientist, who constructed mathematical models in medicine. He has studied and taught Yoga, Judo, Shotokan Karate, Aikido, Qigong, Praying Mantis Kung Fu, and Tai Chi. Dr. Eisen studied Chinese Medicine through apprenticeships and correspondence courses. His new Amazon Kindle and hard copy books “Healthy Exercise for Seniors and Non-Athletes” describes classical Yoga, Tai Chi and Qigong to encourage practitioners to learn more about these arts. For more information about Dr. Eisen please visithttp://kungfutaichiqigong.com .

Marty Eisen, PhD, is a retired scientist, who constructed mathematical models in medicine. He has studied and taught Yoga, Judo, Shotokan Karate, Aikido, Qigong, Praying Mantis Kung Fu, and Tai Chi. Dr. Eisen studied Chinese Medicine through apprenticeships and correspondence courses. His new Amazon Kindle and hard copy books “Healthy Exercise for Seniors and Non-Athletes” describes classical Yoga, Tai Chi and Qigong to encourage practitioners to learn more about these arts. For more information about Dr. Eisen please visithttp://kungfutaichiqigong.com .

Pingback: How meridians relate to Tai Chi | The Tai Chi Notebook