Overview of Best Practices in Taiji

by © Yang Yang

事半功倍: shi ban gong bei

If you study something—anything—in an efficient way, you can learn it in a fraction of the time. (-Chinese Proverb, literally “half the work, double the result.”)

A definition of “best practices” is a beginning point for this topic. I would define “best practices” as “those exercises which allow one to realize the maximum possible results in the shortest amount of time.” According to this definition, “efficient” is essentially synonymous with “best.” Throughout this paper I will therefore use the term “efficient” in place of “best.”

A definition of “best practices” is a beginning point for this topic. I would define “best practices” as “those exercises which allow one to realize the maximum possible results in the shortest amount of time.” According to this definition, “efficient” is essentially synonymous with “best.” Throughout this paper I will therefore use the term “efficient” in place of “best.”

To design the most efficient route, one must also, of course, know the desired destination. The most efficient Taiji practices are intelligible only in terms of the desired goals of Taiji practice. We must first begin, then, with an understanding and recognition of the purpose or benefits of Taiji practice.

Potential Benefits of Taiji Practice

Table 1 summarizes some of the potential benefits of Taiji practice. I have divided the benefits into primary, secondary, and holistic categories. Although these categories are certainly not mutually exclusive, Taiji was created as a martial art, and so specific benefits that yield improvements in self-defense skill are listed as primary, while other specific therapeutic benefits are listed as secondary and broader benefits as holistic. By no means is this categorization intended to lessen the importance of any potential benefit—it is only to emphasize why the core exercises that constitute Taiji practice were initially created. The primary benefits of Taiji training are the skill variables that the Taiji training system was designed to enhance. Postural control and balance, flexibility, coordination, agility, strength and power, sensitivity and awareness, reaction time, and confidence—these are the gong, or essential foundational skills, developed through Taiji practice. They are the support and foundation for technique and therefore indispensable for martial skill—hence the many famous sayings in the internal martial arts tradition emphasizing the priority of gong, or foundation practice (as directly opposed to martial technique or trickery). At the same time, these benefits are fundamentally health issues, and understanding the primary purpose of Taiji practice serves to dispel any confusion or differentiation as to whether Taiji is a martial art or health exercise.

Certainly if you begin Taiji practice hoping to improve or cure a specific medical condition, then that benefit is primary, not secondary, to you. Indeed, throughout Chinese martial arts history, many of the most famous practitioners were initially motivated to practice because of poor health. The holistic category lists benefits that are perhaps the least expected and most difficult to quantify, but sometimes recognized as the most significant in people’s lives.

Table 1

Primary (Skill-Related) Secondary (Other Therapeutic) Holistic

– Postural control/balance – Digestion/bowel function -Avoidance or repair

-Flexibility -Cardio-respiratory function of stress related

-Coordination -Immune system function injuries/illness

-Agility -Prevention or treatment of -Social interactions

-Strength/Power -Cognitive function (eg attention) /sense of community

-Sensitivity/Awareness -Prevention of osteoporosis – Spiritual development

-Reaction Time – Improvement in Sclerosis patients (Calmness/tranquility)

-Confidence – Quality of sleep

The most efficient Taiji curriculum is that which will effectively and quickly yield improvements in these variables. At the same time, no program is broadly effective unless it is attractive to and adhered by the participants. The duration, frequency, and overall level of intensity and complexity of practice, and perceived improvement by each participant, are all variables affecting the rate of adherence. In short, any intervention or exercise must be enjoyed, and the participants must recognize the benefits.

Essential Curriculum

While the slow movement that is most commonly recognized as Taiji is certainly a cornerstone of Taijiquan training, it is only one aspect of the art. Paradoxically, one purpose of the slow movement is to increase both speed and accuracy. Chinese philosophy states that yin and yang are mutually dependent and evolve into one another. If you want one, you should start with its opposite—extreme hardness is born from extreme softness, extreme quickness comes from slowness. Of course, slow movement by itself is not so complete that it can efficiently yield all the benefits of the internal martial arts. Through the centuries, three pillars of Taiji practice have evolved to form an efficient curriculum:

Qigong—Principally wuji sitting and standing meditation

Taiji form—Mainly slow movement practice

Push-hands—Two-person balance, strength, and reaction training

It is important to know that these exercises are interrelated and synergistic—each exercise builds upon skills developed from the others, and the combined effects of correct practice of all exercises are greater than practice of individual exercises.

Sitting and Standing Qigong Meditation

Sitting and standing meditation are common foundation practices for all of the internal martial arts of China. A famous saying in the internal martial arts tradition states:

不静不见动之奇: Bu jing bu jian dong zhi qi.

If you don’t have quiet or tranquility, you will never see the miracle of moving.

Standing Meditation

Wuji zhuang (无极桩), or standing meditation, is translated as “standing pole” exercise and is the basis for Taiji movement. In fact, the Taiji form movement is often referred to as “moving pole” (huo zhuang, 活桩), highlighting that Taiji movement evolves from practicing standing wuji zhuang. Both the classical literature of Taijiquan and the oral tradition of the internal martial arts repeatedly emphasize that wuji zhuang precedes Taiji movement. Chapter Seven, “Training Methods for Sparring,” of The Yang Family Forty Chapters, begins with this point:

Wuji zhuang (无极桩), or standing meditation, is translated as “standing pole” exercise and is the basis for Taiji movement. In fact, the Taiji form movement is often referred to as “moving pole” (huo zhuang, 活桩), highlighting that Taiji movement evolves from practicing standing wuji zhuang. Both the classical literature of Taijiquan and the oral tradition of the internal martial arts repeatedly emphasize that wuji zhuang precedes Taiji movement. Chapter Seven, “Training Methods for Sparring,” of The Yang Family Forty Chapters, begins with this point:

In central equilibrium (what is commonly called “standing pole”), the feet develop root, and then you may study the four sides and advance and retreat [emphasis added]. (Wile, 1996).

Well-known sayings within the internal martial arts community further assert:

练拳不站桩,吃饭没粮仓: Lian quan bu zan zhuang, chi fan mei liang cang.

Practicing form (external movement) without practicing standing pole is like eating food with no grain in the storage bin.

百动不如一静,百练不如一站: Bai dong bu ru yi jing, bai lian bu ru yi zan.

One hundred movements are not as good as one stillness; One hundred practices are not as good as one standing (pole).

Sitting Meditation

Taiji is a fusion of existing martial arts with Daoist philosophies and qigong meditation practices, and sitting meditation has likely always been an integral aspect of Taiji practice. All modern forms of Taiji trace their origins to Chen Wanting (1600–1680), who is credited with creating what is now referred to as the Chen family style of Taiji. Chen Wangting himself referred to his study of the Huangting Jing, an esoteric meditation manual that is part of the Daoist Canon. In Chen Wangting’s own words:

Taiji is a fusion of existing martial arts with Daoist philosophies and qigong meditation practices, and sitting meditation has likely always been an integral aspect of Taiji practice. All modern forms of Taiji trace their origins to Chen Wanting (1600–1680), who is credited with creating what is now referred to as the Chen family style of Taiji. Chen Wangting himself referred to his study of the Huangting Jing, an esoteric meditation manual that is part of the Daoist Canon. In Chen Wangting’s own words:

Recalling past years, how bravely I fought to wipe out the enemy troops, and what risks I went through! All the favors bestowed upon me are now in vain! Now old and feeble, I am accompanied only by the book of ‘Huang Ting.’ Life consists in creating actions of boxing when feeling depressed, doing fieldwork when the season comes, and spending leisure time teaching disciples and children so that they can become worthy members of the society. (Feng, Feng, and Chen, 1984).

Discussion of efficient meditation practice is beyond the scope of this paper. However, a single passage of the Huangting Jing does communicate the essence of meditation. This passage says that “hiding” oneself (fu) in Great Darkness results in “seeing one’s own form” (jian wu xing). This inward looking, in quiet contemplation with the ultimate goal of self-realization, is the essence of meditation espoused by advanced practitioners of all the world’s great spiritual traditions.

Sitting and standing meditation are related, but do yield different benefits and are both essential components of traditional Taiji training. Both are “mind/body” integrative exercises of the nervous system and both strengthen core musculature—upon which the mechanics of Taiji movement fundamentally rely. However, in general, sitting meditation is relatively more directed to the former and standing to the latter. The standing and sitting meditation exercises are so crucial to efficient Taiji practice that it is precisely these exercises that were omitted from public teaching when the goal was to preserve the “secret” of the art within a small, select group of family members or disciples. These practices are now an “open secret,” but little information has yet been disseminated as to why they are important, and almost none of the current Taiji research has even mentioned them.

In a recent study at the University of Illinois, the Taiji/qigong effect was significant for balance and lower body strength two months after beginning an intervention (Yang et al, 2006). The seven-movement choreographed Taiji form taught during the intervention was not memorized by the participants until the end of the fourth month, therefore much of the credit for the rapid improvement in strength and balance must be attributed to the sitting and standing meditation component of the intervention curriculum. (A study comparing the effects of Taiji form, standing and sitting meditation, and the combined effects of both, would be interesting. What is certain is that traditional Taiji teachings, as well as the traditions from other internal martial arts, assert that the standing and sitting meditation practices are important aspects of practice.)

Choreographed Form Movement

Many different “styles” of Taiji have evolved over the past century. Chen, Yang, Sun, Wu, and Wu (Hao) are all considered orthodox styles of Taiji form. The famous martial artist Yang Luchan (1800-1873) was the first “outsider” to learn the art from the Chen family. His grandson, Yang Chengfu (1883-1936), is generally credited with standardizing the form now known as the Yang Family large frame. Yang Chengfu’s modified form was the first to be popularized throughout China and the world.

Although the different forms vary in outward appearance, the principles of the movements remain the same. Understanding the mechanics of the movement—as opposed to memorizing styles of choreography—is what is important in understanding Taiji movement. Once the movement is understood, any movement can be done as Taiji movement. Hence the “style” or outward appearance of choreography is ultimately unimportant, but the principles of practice and mechanics of movement are essential and define “Taiji movement.”

Even if the principles of practice and mechanics of movement are correctly understood, differences in the complexity of movement and range of motion should be considered. For beginning practitioners in general, and older adults in particular, the following principles should apply:

The form movement should not be overly complicated. The original Chen style form, for example, contains relatively complicated silk reeling motions that can only be performed correctly, or even understood, by adept practitioners. These motions are not necessary to begin to learn the art and realize benefits of practice and, in my experience, only confuse beginning practitioners. For this reason, I have omitted the advanced movements when teaching the Chen form to beginning students of any age. I believe that the omission of these advanced movements was a significant factor in allowing the modified form taught by Yang Chengfu to reach a mass audience.

While the truly complex movement should be omitted, challenging postures, such as kicking motions requiring single leg stance or backwards walking motions, should be retained to challenge healthy participants of any age.

The range of motion should be as large as comfortably allowed. A well known saying within the Chen family tradition asserts “From big to small.” A similar saying exists in Chapter 28 of the Yang Family Forty Chapters: “First practice expanding, then look to compacting” (Wile, 1996b). Although smaller and smaller circles are possible as advanced stages of form practice, in order to initially learn the movement, and to increase range of motion and physical ability, it is helpful to first practice with larger motions. Once you understand and can do the movement, you can perform any given circular movements in any radius—there is absolutely no difference in the mechanics of how the movement is generated.

Some believe that a smaller frame form version is better suited for older or less physically fit persons, while a big frame form is more fitting for the younger, stronger, and more martially minded persons. While it is certainly true that the range of motion must be adjusted according to physical capability of beginners, it is also true that, as just explained, smaller movements can represent a higher level of achievement. Whether the practitioner’s interest is in health or martial arts, it is advisable for beginners to gradually increase the range of motion of form movements to improve physical capabilities. The principle of “from big to small” applies not only to arm motion, but to all body movement. Within the comfortable limit of ability, each practitioner should approach the maximum comfortable limits of waist turning and weight shifting during form practice. In so doing, you will not only increase range of motion about the body joints, but also increase the comfortable range of motion within the base of support, effectively increasing the radius about which you are able to maintain balance.

A variety of directional movement should be included in the choreography. It is said that Taiji is practice of the “Thirteen movements.” The thirteen movements are comprised of the “eight forces” (peng/lu/ji/an/cai/lie/zhou/kao) and the “five directions” (advance, retreat, left, right, and central equilibrium). In essence, peng/lu/ji/an/cai/lie/zhou/kao are individual motor skills that, in combination with the five directions, represent all possible range and direction of human movement and force exertion.

A variety of directional movement should be included in the choreography. It is said that Taiji is practice of the “Thirteen movements.” The thirteen movements are comprised of the “eight forces” (peng/lu/ji/an/cai/lie/zhou/kao) and the “five directions” (advance, retreat, left, right, and central equilibrium). In essence, peng/lu/ji/an/cai/lie/zhou/kao are individual motor skills that, in combination with the five directions, represent all possible range and direction of human movement and force exertion.

It is well recognized that the traditional long forms must be considerably abridged for Taiji to appeal to a mass audience, and nearly all styles of Taiji now advertise short forms for mass consumption. When distilling the forms, however, Taiji instructors should be careful to select a wide variety of directional movement to challenge healthy practitioners of any age. Simply repeating the same or similar movements will yield limited benefit in mind/body connection.

Postures that are potentially injurious to the knees should be avoided. Knee injuries are not uncommon among Taiji practitioners. According to Taiji principles, the knees should be slightly bent. However, beginning students of any age should not be encouraged to practice in lower postures. Besides violating basic Taiji principles, lower stances will likely result in an injury to the knees. Similarly, instructors should emphasize correct footwork so that the knees are not stressed during form movement. The simple postural principle is that the stance should always be relaxed and natural—this requires constant stance adjustment during form practice.

Again, these differences in the complexity of movement and range of motion are applicable to beginners of any age, and are mentioned here as a variable subset of the general principles of Taiji practice and mechanics of Taiji movement, which are assumed familiar to any instructor.

Push-Hands

Although push-hands is a pillar of Taiji practice and is essential to realize the maximum possible benefits of practice, correct practice does require a foundation of skill developed through standing and sitting meditation and form practice. I do believe that push-hands can be practiced and enjoyed by older adults, but there is little purpose in introducing this practice at the beginning stages of an intervention. Further information concerning the purpose and interrelated nature of the sitting and standing meditation, form, and push-hands exercises, including hypothesized mechanisms, are detailed in Yang 2005.

Intensity and Duration of Intervention/Exercise

All of the practices of Taiji are qigong, or energy gathering/nurturing exercises. In this respect they are considerably different from the “no pain, no gain” mentality of Western exercise regimes. Following practice one feels (or should feel) energized and refreshed. For this reason, practitioners of any age can practice every day, and those who begin to realize the benefits of practice often choose to do just that.

It is traditionally taught that it is better to practice 10 minutes a day than to practice for one hour on the weekend, and better to practice one hour a day than to practice all day once a week. Practitioners should be encouraged to practice daily. Beginning practitioners, however, are limited in what they can practice and frequently only practice during class time. For this reason, intervention studies should provide instruction and/or organized practice several times a week.

The organization of class time will affect the comfortable duration of each class. Alternation of sitting and standing meditation with form practice may help practitioners remain interested and extend instruction/practice time. Also, the inclusion of simple moving qigong exercises as warm-up exercises may add to the perceived variety of the class, and because these movements are simple and repetitious they may provide a means of perceived self-accomplishment or improvement attainable before choreographed form is learned.

Instruction in choreographed form itself should follow the pace of the class, with attention not to exceed the capacity of the participants to memorize the form. Older adults do have a lesser capacity to memorize and retain choreographed movement, and in our experience at the University of Illinois it took four months of 30 minutes of form instruction three times a week for older adults (mean age 80 years) to learn a seven-movement form. Beginning practitioners of any age are often frustrated with their inability to memorize choreographed movement, and all beginners should be encouraged and reminded that it does not matter in the least how soon one can memorize choreography.

Helping Beginning Students to Relax

Perhaps the most important principle of Taiji and qigong practice is relaxation. Indeed, a famous traditional saying succinctly states that relaxation is the mechanism of qigong healing:

气功能祛病,缘由在松静: Qigong neng qu bing, yuan you zai song jing.

Song (relaxation) and jing (tranquility/quietness) are the reasons why qigong can heal you.

However, whether due to the self-induced anxiety of learning choreographed movement and “keeping up with the class,” the anxiety of learning exercise that may be perceived as foreign to Western culture, or simply to the difficulty of releasing habitual tension that has accumulated over a lifetime, it is often hard for beginning practitioners of any age to relax. I recommend that high quality, well composed meditation music be used as an environmental aid to assist beginning practitioners with relaxation.

Teacher Training

Many famous sayings from the internal martial arts tradition do assert the importance of the instructor. To share just a couple:

苦练十年,不如名师一点: Ku lian shi nian, bu ru ming shi yi dian.

One word from a knowledgeable teacher will save ten years of hard practice.

诀窍奥秘, 须经明师口传心授:Jue qiao ao mi, xu jing ming shi kou chuan xin shou.

Tricks of the trade and secrets of practice must be passed on

by sincere instruction from a teacher who understands the art.

However, it is also said that, ultimately, a teacher can only point the direction for student—it is up to the student to make the journey. (Shifu ling jin men, xiu xing zai ge ren, 师父领进门, 修行在个人, which literally means “the teacher will lead you to the door, but it is up to the student to improve.”) Much of the importance of the teacher is to outline efficient curriculum for the student. The single best question a student can ask is “what should I be practicing, and what percentage of my practice time should be spent on each exercise?”

Through organization, effort, and the generosity of knowledgeable teachers, the most efficient practice curriculum can be mass communicated to potential instructors. It should be recognized, however, that such knowledge is a gift of generations of master practitioners who dedicated their lives to Taiji practice—a gift that was a zealously guarded secret until not too long ago.

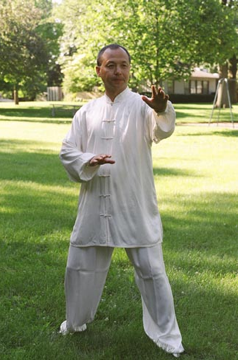

Yang Yang, Ph.D.- is one of the few individuals who are recognized within the traditional Taiji and Qigong community as a master practitioner and instructor, as well as an academic researcher who’s using western science to explore evidence-based Eastern philosophy and healing arts. He is author of the highly acclaimed book “Taijiquan: The Art of Nurturing, The Science of Power”, and in 2006 was honored as the “Qigong Master of the Year” at the 9th World Congress on Qigong and Traditional Chinese Medicine. Yang trained in China under several of the 18th generation grandmasters of the Chen style – Chen Zhaokui, Gu Liuxin, and Feng Zhiqiang. He was a three-time Taiji champion at the Shanghai collegiate tournament and former instructor at the Shanghai Chen Style Taiji research association. To understand the power and mechanics of Taiji and Qigong beyond traditional explanatory frameworks, Master Yang completed a doctorate degree in kinesiology at the University of Illinois, where he remains as an adjunct faculty. Dr. Yang is currently the Director of the Center for Taiji and Qigong Studies (www.centerfortaiji.com) in New York City.

Yang Yang, Ph.D.- is one of the few individuals who are recognized within the traditional Taiji and Qigong community as a master practitioner and instructor, as well as an academic researcher who’s using western science to explore evidence-based Eastern philosophy and healing arts. He is author of the highly acclaimed book “Taijiquan: The Art of Nurturing, The Science of Power”, and in 2006 was honored as the “Qigong Master of the Year” at the 9th World Congress on Qigong and Traditional Chinese Medicine. Yang trained in China under several of the 18th generation grandmasters of the Chen style – Chen Zhaokui, Gu Liuxin, and Feng Zhiqiang. He was a three-time Taiji champion at the Shanghai collegiate tournament and former instructor at the Shanghai Chen Style Taiji research association. To understand the power and mechanics of Taiji and Qigong beyond traditional explanatory frameworks, Master Yang completed a doctorate degree in kinesiology at the University of Illinois, where he remains as an adjunct faculty. Dr. Yang is currently the Director of the Center for Taiji and Qigong Studies (www.centerfortaiji.com) in New York City.

7 Responses to Overview of Best Practices in Taiji