Ever woken up suddenly at 2:30 AM after a rich meal or a stressful day? According to Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), this isn’t just a random occurrence. Your body might be sending you a signal based on an ancient concept known as the Chinese Body Clock, or the theory of the “Horary Cycle.”(子午流注)

Many people report a curious pattern: waking up repeatedly at certain times of night, feeling hungry late in the evening, or experiencing an energy crash in the early afternoon….

From the perspective of TCM, these patterns may reflect a mismatch between our daily habits and the body’s natural time-based rhythms—a concept known as the Chinese Body Clock.

Far from being mystical, this ancient framework offers a surprisingly practical guide for sleep, eating, movement, and energy management—especially when combined with practices such as Qigong.

What Is the Chinese Body Clock?

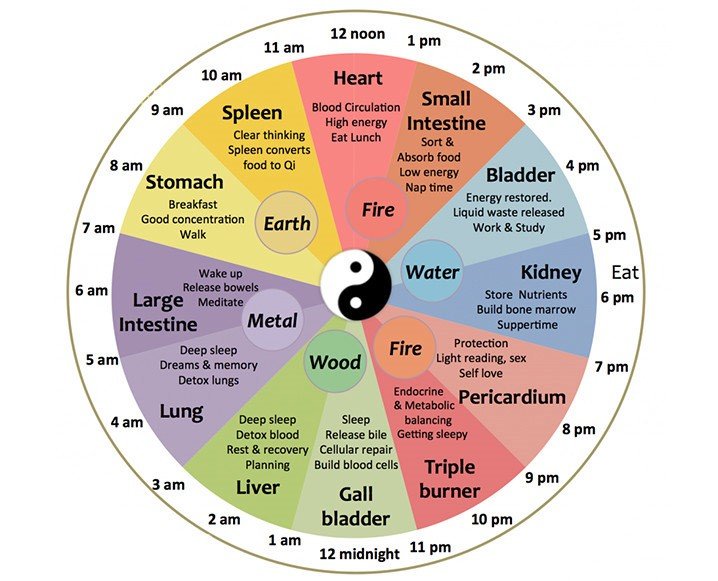

The Chinese Body Clock is a foundational TCM model describing how functional energy (Qi) circulates through the body’s 12 primary organ systems over a 24-hour period.

Each organ system is associated with approximately two-hour window during which its physiological and regulatory activity is believed to be at its peak.

Think of it as an internal maintenance schedule:

- Certain times favor digestion

- Others support detoxification and tissue repair

- Others are ideal for focus, rest, or emotional regulation

When daily activities roughly align with this rhythm, the body tends to function more smoothly. When we consistently work against it with late-night eating, irregular sleep, constant stimulation—imbalance becomes more likely.

Where Does This Idea Come From?

1. Classical Chinese Medicine

The roots of the Body Clock trace back over 2,000 years to the Huangdi Neijing (Yellow Emperor’s Inner Classic), which emphasizes that: “Qi moves through the organs according to time.”

TCM views the body as a dynamic system, not a static machine. Physiological processes rise and fall throughout the day, coordinated through the meridian network, as well as the Jing Jin (经筋 –muscle–tendon) responsiveness aligned with meridian circulation.

This time sensitivity explains why traditional practices such as acupuncture, herbal therapy, tui-na and Qigong often emphasize when an intervention is applied—not just what is applied.

2. Modern Science: Circadian Biology

From a Western scientific perspective, the Chinese Body Clock aligns closely with findings from:

- Circadian rhythm research

- Chronobiology

- Chronomedicine

We now know that many bodily functions follow predictable daily cycles, including:

- Hormone secretion (cortisol, melatonin)

- Liver enzyme activity

- Immune response

- Gastrointestinal motility

- Cardiovascular events

While modern science does not use the meridian framework, it strongly supports the core insight behind time-based medicine:

timing matters.

Is There Scientific or Clinical Support?

It is important to be precise: The Chinese Body Clock itself was not derived from modern randomized controlled trials. However, many of its observations are consistent with contemporary physiological data. Examples include:

- Increased bowel activity in the early morning

- Enhanced liver detoxification during deep nighttime sleep

- Higher asthma symptom frequency in early morning hours

- Time-dependent effectiveness and side effects of medications

In other words, the Body Clock can be understood as an early systems-level model of biological timing—empirical, observational, and now increasingly echoed by modern research.

The 12 Time Periods: Muscle–Tendon Time — Musculoskeletal Focus — Practical Guidance

Important clarification: The following 12 time periods reflect Jing Jin (经筋) responsiveness aligned with meridian circulation, not literal Zang–Fu organ activity. This is the traditional source model, emphasizing muscle–tendon, fascial, postural, and movement-related disorders rather than internal organ pathology.

In classical usage, these time windows describe when a meridian’s sinew system is most reactive, vulnerable, or therapeutically accessible — particularly for pain, stiffness, spasm, weakness, or injury.

They should not be interpreted as strict organ-diagnostic clocks!

Below is a simplified, user-friendly guide with everyday applications of TCM body clock.

11:00 PM – 1:00 AM | Gallbladder Muscle–Tendon (子时 Zi Shí · Midnight)

Primary focus: lateral hip, flank, IT band, decision-related tension patterns. Common presentations: hip tightness, temporal headaches, side-lying discomfort

- Supports fat metabolism and cellular repair

- Best practice: be in bed before 11 PM

- Example: Regularly staying up past midnight may contribute to poor decision-making, irritability, or digestive discomfort.

1:00 – 3:00 AM | Liver Muscle–Tendon (丑时 Chǒu Shí)

Primary focus: medial leg, adductors, pelvic floor, tendon elasticity; Common presentations: cramps, tendon tightness, nocturnal muscle tension.

- Blood cleansing and metabolic regulation

- Waking during this window often correlates with stress, alcohol intake, or emotional overload.

3:00 – 5:00 AM | Lungs muscle–tendon (寅时 Yín Shí)

Primary focus: chest, shoulder girdle, biceps, breathing-related tension; Common presentations: shoulder restriction, upper chest tightness.

- Oxygen exchange and autonomic regulation

- Example: Early-morning coughing, shallow breathing, or sadness may relate to lung-related imbalance.

5:00 – 7:00 AM | Large Intestine muscle–tendon(卯时 Mǎo Shí · Sunrise)

Primary focus: neck, trapezius, forearm extensors; Common presentations: morning neck stiffness, elbow pain

- Ideal time to wake, hydrate, and have a bowel movement

- Example: A glass of warm water and a calm morning routine often improve regularity more than laxatives.

7:00 – 9:00 AM | Stomach muscle–tendon (辰时 Chén Shí)

Primary focus: anterior body line, quadriceps, tibialis anterior; Common presentations: knee pain, anterior shin tightness.

- Peak digestive capacity

- Practical rule: Eat breakfast like a king, dinner like a pauper.

9:00 – 11:00 AM | Spleen muscle–tendon (巳时 Sì Shí)

Primary focus: medial thigh, core support, postural endurance; Common presentations: fatigue-related postural collapse, inner-leg weakness.

- Best time for learning, teaching, and analytical work

- Example: Schedule lectures or complex tasks here when possible.

11:00 AM – 1:00 PM | Heart muscle–tendon(午时 Wǔ Shí · Noon)

Primary focus: upper chest, medial arm, coordination and integration; Common presentations: arm tension, chest restriction, psychosomatic tightness.

- Supports blood flow and joy

- Eat lunch, socialize, avoid intense stress.

- Qigong or massage for lowing blood pressure, and for heart health

1:00 – 3:00 PM | Small Intestine muscle–tendon (未时 Wèi Shí)

Primary focus: scapula, posterior shoulder, fine motor coordination; Common presentations: scapular pain, shoulder instability.

- Common energy dip time

- Example: A 15–20 minute nap can restore clarity better than caffeine.

3:00 – 5:00 PM | Bladder muscle–tendon (申时 Shēn Shí)

Primary focus: posterior chain, spine, hamstrings, calves; Common presentations: low back pain, stiffness, fatigue-related strain.

- Energy rebounds; great time for an afternoon tea

- Stay hydrated; this is a good window for focused work.

5:00 – 7:00 PM | Kidneys muscle–tendon (酉时 Yǒu Shí · Sunset)

Primary focus: lumbar spine, deep stabilizers, Achilles tendon; Common presentations: chronic low back weakness, heel pain.

- Ideal for gentle exercise, Qigong, walking

- Kidney-nourishing qigong or exercises

- Dinner should be lighter and warming.

7:00 – 9:00 PM | Pericardium muscle–tendon (戌时 Xū Shí)

Primary focus: forearms, wrist flexors, protective tension patterns; Common presentations: wrist pain, repetitive strain injuries.

- Emotional bonding and calming activities

- Example: Conversation, reading, gentle stretching.

9:00 – 11:00 PM | Triple Burner muscle–tendon (亥时 Hài Shí)

Primary focus: global fascial regulation, temperature and fluid-related tension; Common presentations: generalized stiffness, coordination fatigue.

- Regulates metabolic and endocrine balance

- Reduce screen exposure, dim lights, prepare for rest.

Clinical note:

Internal Zang–Fu functional rhythms exist as a separate but related system and should be understood differently from Jing Jin (muscle–tendon) time. A simple and commonly observed example involves nighttime urination. In TCM, the late evening and early night hours—from 9:00 PM to 3:00 AM—are associated with how the body manages water and fluids during rest. During this period, the Bladder, Kidneys, and San Jiao work together to store fluids, regulate urine, and maintain balance while the body sleeps. When this system is not yet mature, weakened, or under strain, people may wake to urinate at night. This helps explain why children may experience bedwetting, why bladder leakage is more common with aging, and why many men with prostate-related issues are often awakened to urinate during these hours. Rather than indicating a single organ problem, this pattern reflects the body’s overall ability to hold and regulate fluids during sleep.

How to Apply This Effectively Without Stress

1. Focus on the “Big Three” — You don’t need perfection. Start here:

- Sleep: Aim for lights-out before 11 PM

- Meals: Bigger breakfast, lighter dinner

- Morning routine: Regular elimination time

2. Integrate with Qigong Practice

- Morning: breathing and lung-focused movements

- Late afternoon: grounding and kidney-supportive practices

- Evening: calming, meditative Qigong

3. Observe, Don’t Force

The Body Clock is a guide, not a rigid rulebook. Time-based health cultivation is a reference system, not a rigid discipline. The goal is gradual alignment, not perfection.

The essence of time-based health cultivation is not blind adherence to the clock, but respectful listening to the body’s natural rhythms.

When we live in harmony with time, health often requires less effort—not more. This is the heart of preventive medicine.

Time-Based Finger and Toe Massage

1. A Practical Extension of the Chinese Body Clock (子午流注)

One of the lesser-known yet highly practical applications of the Chinese Body Clock (子午流注) involve finger and toe massage.

In TCM, the tips of the fingers and toes are where the jing-well points (井穴) of the meridians are located. These points are considered:

- Highly responsive

- Neurologically sensitive

- Clinically useful for acute regulation and symptom relief

When combined with time awareness, stimulation of these distal points can be especially effective.

2. Why Fingers and Toes?

According to TCM, each of the 12 primary meridians either begins or ends at a finger or toe; during its two-hour peak window, that meridian is said to be “in command” (the X meridian is dominant / 当值)

Stimulating the corresponding finger or toe during that time window is traditionally believed to:

- Regulate excessive or deficient Qi

- Calm acute symptoms

- Support emergency or near-emergency situations

(e.g., dizziness, chest tightness, anxiety, digestive distress)

This principle has been widely used in:

- Classical acupuncture

- Pediatric massage (小儿推拿)

- Qigong self-regulation and massage

- Field or emergency first-response techniques

3, How to Apply Finger/Toe Massage Safely

Method (simple and teachable):

- Use thumb and index finger to pinch or press

- Moderate but firm pressure (a little painful)

- Massage for 30–60 seconds, repeat 2–3 times

- Combine with slow nasal breathing

This is not a substitute for emergency medical care, of course, but a regulatory first response while help is on the way or symptoms are mild.

Join us to the weekly Qigong and Longevity practice, every Sunday morning 9:00 to 10:30am, we will teach the details in application of TCM body-clock practice and the specific time-based finger and toe massage for the first response to unexplained pain or discomfort…

Final Thoughts

The wisdom of time-based living is not about believing in a clock—it’s about listening to the body.

When we respect natural rhythms, we often find that health requires less effort, not more.

That, ultimately, is the essence of preventive medicine and self-healing process.

Read more about our Weekly Qigong and Longevity Class at: https://yang-sheng.com/?p=13015

References

- Huang Di Nei Jing (Yellow Emperor’s Inner Classic), translated by Unschuld, P. U.

- Moore-Ede MC, Sulzman FM, Fuller CA. The Clocks That Time Us. Harvard University Press.

- Hastings MH, Maywood ES, Brancaccio M. “The mammalian circadian timing system.” Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2018.

- Smolensky MH, Peppas NA. “Chronobiology, drug delivery, and chronotherapeutics.” Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 2007.

- Liu T and Chen KW, ed. “Chinese Medical Qigong” (2010) London: Singing Dragon Publisher,